OK. Now we are getting somewhere. We will use comprehensible input, but unlike Krashen we will base it on the L1, not on the L2.

And here things improve dramatically, because this idea of using bi-lingual texts to make input comprehensible has been around for centuries. I think the philosopher John Locke started it with his Aesop in the 1660’s or so, then in the 1780’s the Frenchman Dumarsais (Methode Raisonee pour apprendre la langue Latine), then James Hamilton in the 1820s, then in Germany around the 1850’s two Germans Toussaint and Langenscheidt made interlinear translations the basis of their Unterrichtsbriefen series. (I picked this up from a 1908 book by Leopold Bahlsen who says that the Toussaint-Langenscheidt method constitutes a “page of honour in the history of language teaching”, but I haven’t been able to find out much more about it. The German firm Langenscheidt is now an international organisation. Perhaps German users of LINGQ might be able to tell us more.

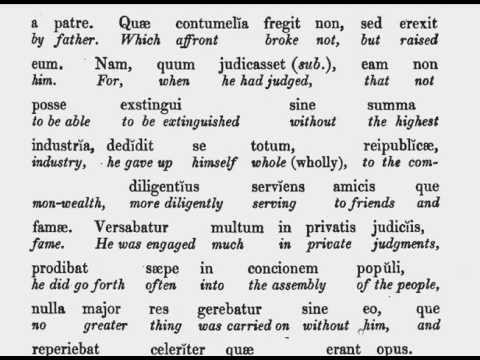

Anyhow, the man who really put this method on the map was James Hamilton. Up till then the interlinear translations had been fairly free, but Hamilton insisted that the student should be able to rely upon each English word as being a faithful rendition of the Latin word above it, so his interlinear translations are completely literal and faithful to the foreign text.

The good news for students of Latin and Greek is that Hamilton and his followers, principally Thomas Clark in the USA, produced interlinear translations for much of Latin literature.

They didn’t do much for Greek (only St John’s Gospel, Homer Iliad 1-6, Xenophon Anabasis and Demosthenes De Corona) but if you can speak French there is a lot of Greek literature available in the “Juxtalineaire” series published by Hachette in the 1880’s.

So there’s tons of Latin and Greek literature available in comprehensible input format. You can download it as PDF from GoogleBooks or buy as print-on-demand reprints.

Here’s a discussion about the Hamiltonian System on HTLAL, with a list of available titles.

http://how-to-learn-any-language.com/forum/forum_posts.asp?TID=26299

And here an example of Evan Milner reading (a bit jerkily) a Hamiltonian interlinear of Cornelius Nepos, vintage 1825.

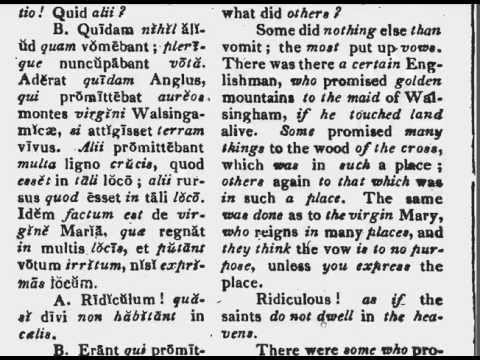

Here he is again, this time reading some of Erasmus’s Dialogues. This time it’s a parallel column bi-lingual text, vintage 1804

An example of a Traduction Juxtalineaire for Greek published by Hachette, This one is Euripides’ Hippolytus, vintage 1848.

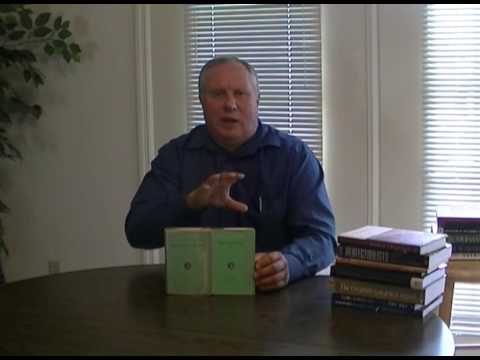

Obviously if we are talking of parallel texts, you need to know about the Loeb Classical Library. This series is published by Harvard and covers most of Greek and Latin literature. If you go to a university Classics course most people will be using Loebs.

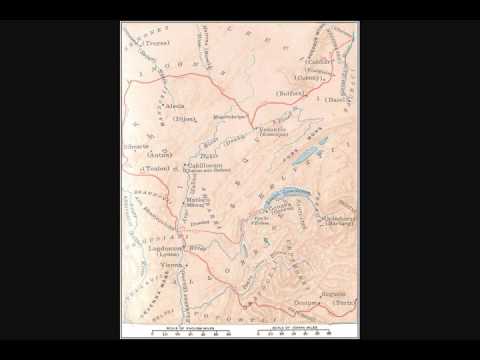

The Loeb has facing pages of Latin and English and the translations are often fairly free, so they are neither specific enough or literal enough for the beginner. So if you wanted, say, to read Caesar’s Gallic War I would buy the Hamiltonian interlinear to help you nail down the grammar with it’s very strict literal translation, but also buy the Loeb for a nice modern Latin text and flowing translation,

Here’s Pastor Steve Waldron to give us a Loeb demo:

and the Hamiltonian interlinear of Caesar on Abebooks

Finally, have to include this one: the totally awesome Charlton Griffin has made Audiobooks of most of the Greek and Roman historians. Here’s his Caesar Gallic War. Turn up the sound to maximum and play the opening full blast!